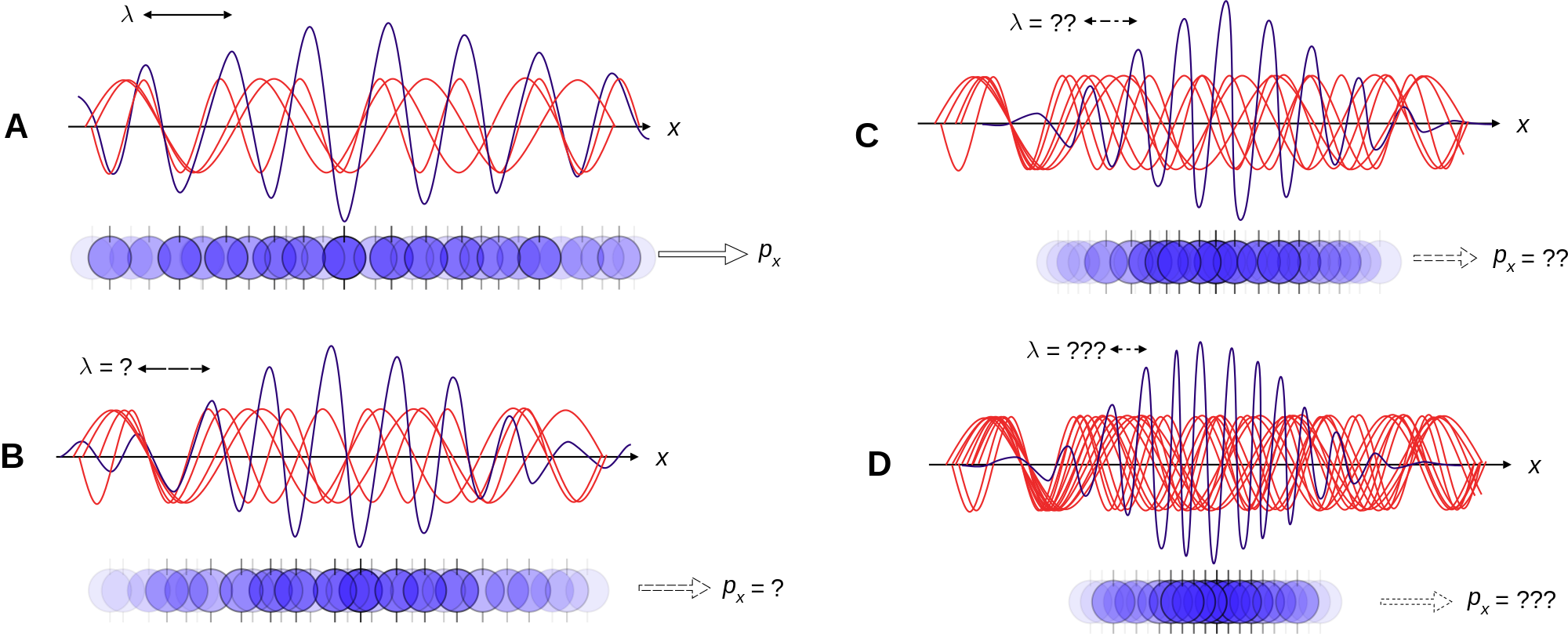

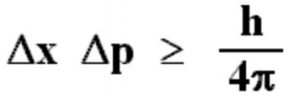

Since quantum mechanics underlies almost all modern technology, the HUP turns up all over the place. Applications in technology implications in philosophy The HUP in one form or another is a useful principle in almost every field of science dealing with very small amounts of matter or energy. In fact, some simple arguments involving the motion of electrons around the nucleus of an atom let us derive the approximate size of an atom as the minimum Δq ≈ 10 -10 meters implied by the HUP. The mass of an electron is extremely small (m ≈ 10 -30 kg) so that ħ/m ≈ 10 -5 on the right-hand-side of equation (1) is no longer ridiculously small. This smallness is why we don’t have to worry about the HUP in everyday life.Īlthough the HUP doesn’t have much to say about speeding tickets, it’s ubiquitous at the scale of atoms and sub-atomic particles. In the units used here, ħ ≈ 10 -34 that is 0.00 … 001, where there should be 34 zeros here. The HUP in its looser form (“you can never be sure of everything”) is thus a consequence of the fact that Planck’s constant is not zero. This means that, although Δq can be as small as you like as long as Δv is large enough, or vice versa, they cannot both be arbitrarily small. Note that the two uncertainties are multiplied together in equation (1), and the result must be greater than some number. Here Δq is the uncertainty in the position of the particle (in metres), Δv is the uncertainty in its speed (in metres per second), m is its mass in kg, and ħ is a constant ( Planck’s constant divided by 2*pi). Precisely uncertainįor the example given earlier, Heisenberg’s principle can be precisely stated as: Unfortunately, although quantum mechanics seems fundamental, it’s not simple, and so cannot be encapsulated as a principle. That thing is quantum mechanics, a theory that applies to all forms of matter and energy (as far as we can tell). Heisenberg’s principle is not like that – it’s actually a consequence of something more fundamental. A “ principle”, in science as in everyday life, is a fundamental simple idea from which all sorts of other things can be derived, such as the principle of freedom, or the principle of fairness.

Is it a Principle?īefore getting into the details, one thing to get clear is that Heisenberg’s “uncertainty principle” is not really a principle at all. In the second, there is the HUP that says if you accurately measure the position you will disturb its speed, making it more uncertain, and vice versa. In the first case, there is the HUP that says it is not possible to simultaneously measure position and speed with perfect accuracy. Or I first measure the position, then the speed.” In fact, neither of these options will work, and what rules them out is other forms of the HUP itself. If I want to know both I just measure them simultaneously. You might be jumping up and down at this point and saying “That’s ridiculous. But you will never be able to arrange things so that you can be certain of both its position and its speed. A different experiment would let you predict its speed. It is possible to arrange an experiment so you can predict the position of a particle. The simplest example of the HUP is the following: You can never be certain of both the position and the speed of a microscopic particle. The HUP killed that dream in a very interesting way. Of course, life would be pretty boring if we could always predict what was going to happen next, but for many centuries scientists dreamt they would be able to do this.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)